On March 28, as students at IIT Guwahati celebrated Holi, an undergraduate student was sexually assaulted by a fellow student on campus. The assault was confirmed in a preliminary medical report but denied by the administration. A student was later arrested and charged with rape.

In the same month, a Ph.D. student was expelled by the same institute for a Facebook post that questioned the credibility of the JEE. The institute said he “misinterpreted facts” resulting in “defamation”.

Earlier this month, the alumni body of IIT Gandhinagar issued a statement highlighting the college’s exclusionary measures during the Covid pandemic. Students were being forced to pay a “quarantine charge” if they wanted to use quarantine facilities on campus which, the alumni body pointed out, discriminated against marginalized students. Students were also penalized for failing to meet attendance requirements during the pandemic.

More recently, a professor from IIT Kharagpur was captured on video abusing students from marginalised backgrounds during an online class.

We need to remember that the IITs are well-known for their high suicide rates. Last year during the lockdown, a PhD student died by suicide at IIT Gandhinagar. This is just one of the many things wrong with India’s “premier” institutions. Cases of suicide are deliberately buried in files to enable the institutes to maintain their public image.

The institutes are oppressive and discriminatory, and students have no agency to speak out against the authorities. The high suicide rates stem not only from academic pressure but issues of caste and religion. Compared to central universities like Delhi University, Jawaharlal Nehru University, University of Hyderabad, and Jamia Millia Islamia, the IITs have little or no political space. Elected student bodies have limited power, operating as extensions of the administration.

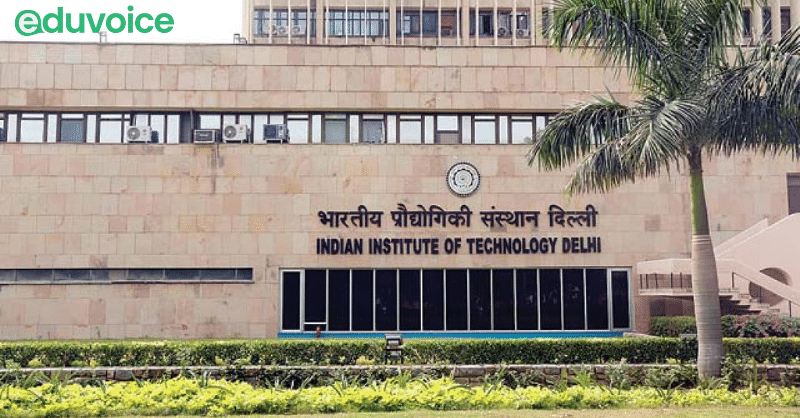

Some students groups have been trying to create space for activism at the IITs, such as APPSC at IIT Bombay, APPSC at IIT Gandhinagar, Chintabar at IIT Madras, Students for Change at IIT BHU, Science Education Group at IIT Kharagpur, and IIT Delhi for Justice, Freedom and Democracy at IIT Delhi. An inter-IIT support group called COSTISA has also attempted to promote progressive politics and campus democracy. However, many of the IITs have already cracked down on these initiatives, urging students to embrace the status quo instead and abandon independent thought.

In 1928, Bhagat Singh wrote a piece on students and politics to address the importance of student participation in political movements. He wrote: “It was the efforts of students and youth that has brought independence to any country which are now free. Will the youth and students of India be able to save the existence of themselves and their country by remaining aloof from the freedom struggle?”

should study, surely study. But along with it, they should also acquire political knowledge and, when required, should not hesitate to jump into the fray and dedicate their lives to this work. Sacrifice their life for the cause.

Singh also wrote that students

So, what are the IITs afraid of? Should students at centres for higher education be involved in politics? Students are voters; therefore, they are already involved in the conventional political process. Students cannot be asked to ignore basic issues of human rights that affect them and their families and be told to focus on their studies instead. This is naïve, an assault on democracy, especially considering the irrational times we live in.

Political leaders and activists tend to emerge from campus politics. They gain trust and cultivate strategic skills and leadership qualities in the process. Student politics facilitates the reinforcement of social ties, the formation of new alliances, the promotion of communal unity, and helps hold the administration accountable. Without it, students will become mindless machines of corporate mills, unable to react to current issues. Or, in the case of the IITs, they become technological zombies.

Interestingly, most politically active students are from the humanities and social sciences disciplines in the IITs, nurtured by a general sense of trepidation against the authorities and their concomitant apparatus. But it’s important for students from other disciplines, primarily science and technology, to get involved. In the 21st century, new and emerging technologies have far-reaching political implications. If we analyze the relationship between science and state politics, we see how the science-state affinity can help shape social dimensions.

Hence, it’s high time for the IITs to equip its science and technology students with space and know-how to familiarise themselves with changing socio-political narratives of the global order rather than confining them to imaginary technological cocoons. It’s also imperative that the student communities stand together for their democratic rights and fight against oppression, both obvious and invisible.

For More Such Articles, News Update, Events, and Many More Click Here