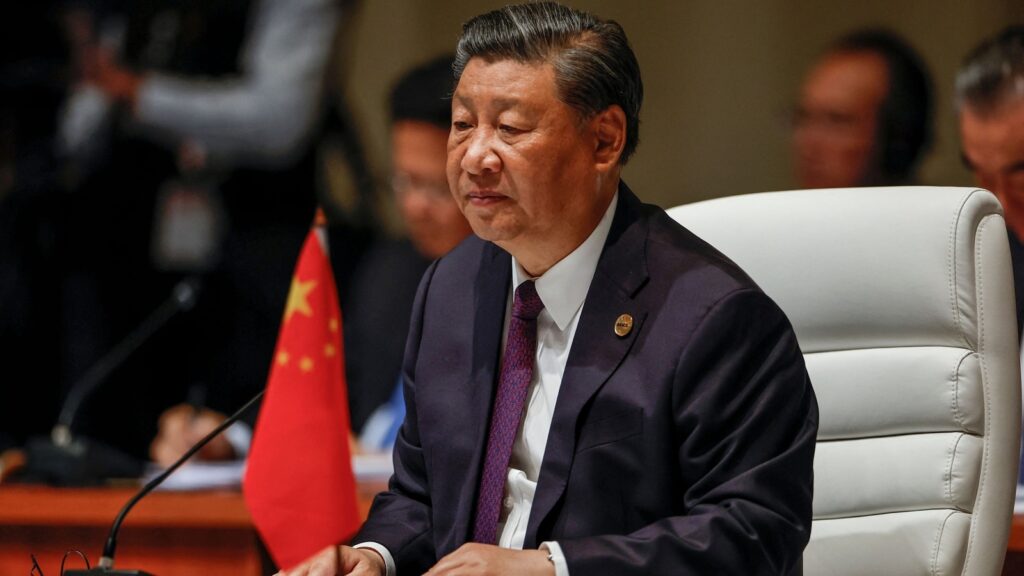

It’s official. China’s president Xi Jinping won’t make it to the G20 summit in Delhi, and Beijing will be represented by the Chinese premier Li Qiang. Whether to attend an international gathering or not is purely a sovereign choice and is dictated by a range of geopolitical, strategic, internal and logistical reasons. But Xi’s decision to skip the summit (it is the first G20 he has missed) also emanates from Beijing’s hubris, particularly its disregard for international cooperation unless China sets the terms, and its increasing unease with India’s posture and position in the world.

There are some who have suggested that Xi’s absence reflects poorly on Indian diplomacy. That’s entirely incorrect. Despite being at the receiving end of Chinese aggression and maintaining a consistent position that the return of normalcy in bilateral ties is predicated on the restoration of peace and tranquillity at the border, Delhi has gone out of its way to keep channels of communication open with Beijing. It has stepped up its diplomatic engagement at various levels; Prime Minister Narendra Modi had brief conversations with Xi in Bali last year and Johannesburg last month; on G20, India extended the same hospitality to the Chinese delegates that it has to others, and it has also sought to work with China on the agenda, finding convergences wherever possible. As G20 president, India could not have done more.

The problem is Beijing. It wants India to pretend that all is well at the border. It isn’t. It wants India to dilute its relationship with the West. Delhi won’t and shouldn’t. It wants to block not just the language around Ukraine in a possible joint communique along with Russia, but also obstruct other elements of the agenda and expects Delhi to toe the line. Delhi won’t. In this backdrop, Xi’s decision not to come is a signal that Beijing does not want India’s G20 presidency to succeed, and in this quest, it is willing to jeopardise prospects for greater international cooperation on a range of economic, financial, environmental and social protection measures. This reflects poorly on China’s great power ambitions. It is an insult to the idea of reformed multilateralism from a country that claims it wants the global architecture to reflect contemporary realities. As a country that has contributed to the debt crisis with its predatory financing practices, when issues of debt relief are on the agenda, it is also an abdication of responsibility. For India, Xi’s absence doesn’t matter; in fact, his presence would have made things awkward given China’s actions at the border. But for the world, it is another sign of Chinese unilateralism.

Embrace independence with quality journalism

Save on HT + The Economist subscription