Amplifying L&D With AI

Welcome back to part five (find part 4 here) of our ongoing exploration of the transformative role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Learning and Development (L&D). As we journey forward, we’re reminded of Steve Jobs’ compelling metaphor, where he likened computers to a “bicycle for our minds“, amplifying our abilities in unprecedented ways. This metaphor elegantly extends to AI in L&D, and in this fifth installment, we shift gears to focus on the fascinating concept of “learning in the flow of work.” As we delve deeper into this concept, we begin to realize that it is not just about learning for the sake of learning, but about learning that is tightly interwoven with work, thereby driving both personal/team growth and organizational performance.

Learning In The Flow Of Work: Navigating The Formal-Informal Dichotomy

Ever pondered the exact definition of learning in the flow of work (Bersin, 2018)? Has it left you scratching your head, wondering if it’s about formal learning at the workplace, learning by doing, or a mix of both? And if so, what would that mix look like? This challenge isn’t just yours, many Learning and Development professionals experience the same conundrum, don’t they?

Most L&D professionals see formal and informal learning as opposites on the learning continuum, but is it truly so cut and dry, or could it be more nuanced? Does this dichotomous way of thinking make it harder to effectively define and implement learning in the flow of work? A vast majority of L&D professionals perceive formal and informal learning as two opposing ends of the learning continuum.

Figure 1: Contrasting characteristics of formal and informal learning

Such binary thinking is explained by the tendency to define informal learning in terms of what formal learning isn’t (Colley, et al., 2003). This dichotomy appears ubiquitous across blogs, articles, books, and academic literature authored by L&D professionals and scholars alike (Council of Europe; Cross, 2007).

Has this ever made you ponder the effectiveness of “learning in the flow of work”? Are we talking about formal learning (at the workplace) facilitated by microlearning, coaching, workplace training, learning communities, and more? Or is it informal learning, fostered through performance support, communities of practices, etc.? The portrayal of formal and informal learning as antonyms spark competition.

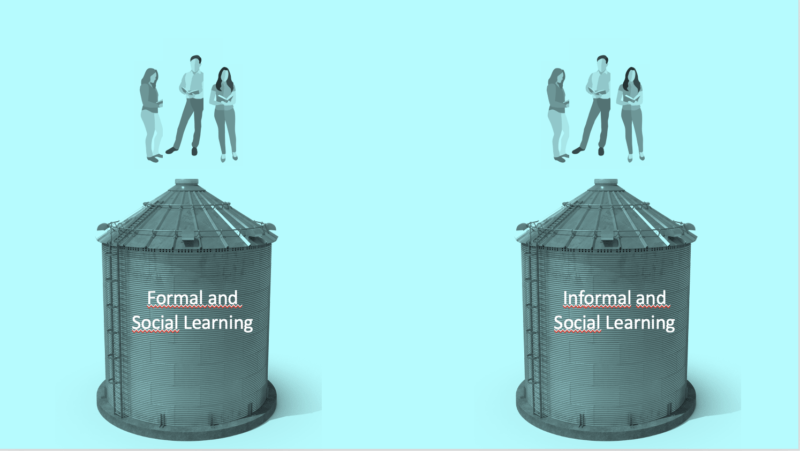

The Silos Of Formal And Informal Learning

The participants in the debate on formal versus informal learning act as if two silos of learning exist in organizations. A “silo” is defined by Merriam-Webster Dictionary as “an isolated group or department that functions in a way that hampers communication and collaboration.” The two silos of learning in organizations are:

- Formal and social learning

- Informal and social learning

Figure 2: Two silos of learning in organizations, visible for L&D.

It’s worth emphasizing that for both formal and informal learning, social learning is inextricably linked as a social learning process (Bandura, 1977; Lave and Wenger, 1991). Therefore, there is no question of a third silo: social learning. The consequences of silo formation in organizations, which also applies to learning, are:

- Competition with only the others within the silo

- Misunderstandings due to poor communication (insufficient mutual understanding)

- Blockage of knowledge development and sharing because each silo functions independently

- Loss of performance, because the power of each silo works against each other, not with each other

Unboxing Formal And Informal Learning

The fact that there are no hard differences between formal and informal learning has been known since the beginning of this century. Colley, et al., concluded in 2003:

Learning is often thought of as “formal”, “informal” or “nonformal.” This report suggests that these are not discrete categories, and to think that they are is to misunderstand the nature of learning. It is more accurate to conceive “formality” and “informality” as attributes present in all circumstances of learning.

To clearly distinguish formal from informal learning, Cross (2007) has used the metaphor of the cyclist (formal learning) and the bus passenger (informal learning). In this metaphor, the degree of freedom and structure play a decisive role in accentuating the differences between formal learning (less freedom and more structure) versus informal learning (more freedom and less structure). This is a useful metaphor for learning in free time, but does not apply to informal learning through work.

Billet (2002) argues that this is not a useful distinction:

Workplaces are in fact highly structured environments for learning: as with educational institutions, in workplaces, there are intentions for work practice, structured goal-directed activities that are central to organizational continuity, and interactions and judgments about performance that are also shaped to those ends. Therefore, describing learning through work as being “informal” is incorrect.

Billet’s conclusion turns the thinking about oppositions between formal and informal learning on its head. It is no longer tenable to maintain that formal learning predominantly proceeds in a planned and structured manner, as opposed to free and spontaneous informal learning through work in organizations. Cross’s evocative metaphor of the cyclist and the bus passenger no longer applies. Freedom and structure of learning are no longer the defining characteristics to denote differences between formal and informal learning.

The Workplace Also Directs Learning–The Foundation For Learning In The Flow Of Work

To quote Billet (2002): “All learning takes place within social organizations or communities that have formalized structures. For example, learning at work is structured by the formal arrangements of the workplace.”

The (social) structures that partly guide learning in organizations are at least as determinative for the form, content, and outcomes of the learning process as the planned and structured learning processes in education (Billet, 2003). Examples of steering in organizations are goals for individuals and teams, desired outcomes, work processes, standards, methods, safety, measurements, the management style, balance score cards, the working environment, laws and regulations, the social structure of society, and so forth.

Case Study: Learning In The Flow Of Work At TechX Corp.

At TechX Corp., a cutting-edge software company, there’s a saying that goes around: “Learning is in our DNA.” But the reality is that it isn’t just in the DNA, it’s in the very fabric of their work environment. One example is the implementation of a new safety protocol. Instead of a simple one-off training session, the protocol was incorporated into the daily operations. Regular checks, reminders, and after action reviews ensured that the protocol became part of the team’s everyday routine, allowing them to learn and adapt in a real-world context.

Additionally, TechX’s management style promotes continual learning and improvement. Managers set clear expectations, but also provide space for exploration and problem-solving. This balance of structure and flexibility encourages team members to learn from their experiences and apply their knowledge in novel ways. In essence, TechX Corp. is a prime example of how a work environment can guide and direct learning. With the right structures in place, learning becomes an integral part of the work, thereby creating a learning-oriented workflow that’s as dynamic as the industry itself.

Redefining The Concept Of Learning In The Flow Of Work

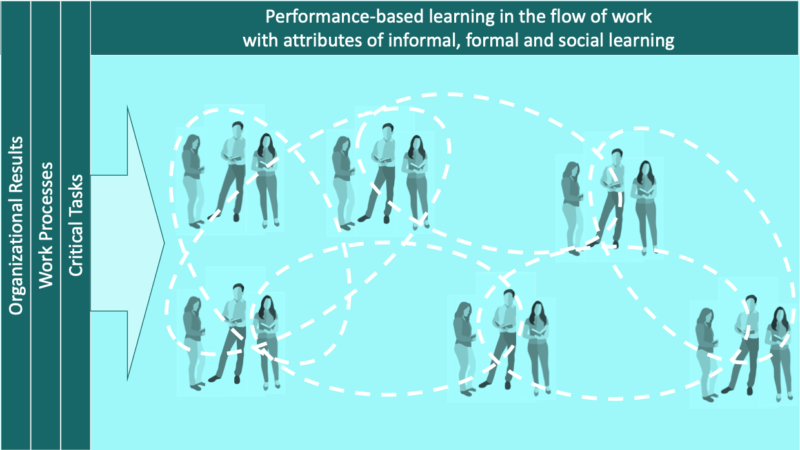

Hinging on the unification of learning silos and steering the symbiosis of work and learning within organizations, “performance-based learning in the flow of work” can be encapsulated as:

Working and deriving learning from [work], resulting in a more effectively arranged work environment where performers and teams, through shifts in behavior and mental models, operate more efficiently, effectively, and enjoyably, gaining new knowledge from this approach. In real-world scenarios, this learning process is facilitated through an effective blend of evidence-informed learning in the flow of work solutions. Essential catalysts for learning in the flow of work include reflection, feedback, and action during socialization in the team and the organization, participating in improvement teams, addressing complex problems, facing challenges, driving innovation, sharing knowledge both inside and outside the organization, learning from experts and exemplary performers, striving towards desired organizational achievements, and participating in audits, among other things.

The evolution of “performance-based learning in the flow of work” has provided an exciting opportunity for L&D teams to expand beyond the constraints of traditional learning silos. Instead of focusing primarily on formal learning, L&D can now facilitate and support a seamless blend of formal, informal, and social learning experiences, creating a richer, more productive, and adaptive working and learning environment.

Figure 3: The two silos of formal and informal learning form a single entity: performance-based learning in the flow of work.

Examples Of Performance-Based Learning In The Flow Of Work

After action reviews and improvement teams in Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles are great examples of evidence-informed learning in the flow of work across various industries. PDSA is a methodical improvement approach that can be described as follows (Wikipedia):

A continual improvement process, often called a continuous improvement process, is an ongoing effort to improve products, services, or processes. These efforts can seek “incremental” improvement over time or “breakthrough” improvement all at once. Delivery (customer valued) processes are constantly evaluated and improved in the light of their efficiency, effectiveness, and flexibility.

That’s the purpose, as Deming sees, of the PDSA cycle (Edward Deming Institute, 2023): “a systematic process for acquiring valuable knowledge for the continuous improvement of a product, process, or service.”

Case Study: Performance-Based Learning At GreenRoot Agriculture

GreenRoot Agriculture, a sustainable farming initiative, was grappling with inefficient crop yield. They turned to performance-based learning in the flow of work to boost their productivity. They initiated the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle. The “plan” phase involved devising improved irrigation and fertilization techniques. In the “do” phase, these new techniques were implemented in the field. The “study” phase involved comparing crop yields using the new versus the old methods. They noticed an improvement, but identified that soil quality needed additional attention. In the “act” phase, they introduced organic composting and cover crops to enrich the soil. Throughout this process, the GreenRoot team learned while working, adapting their methods based on feedback and results, leading to an overall improvement in crop yield and farming efficiency. This practical application of the PDSA cycle demonstrated the power of performance-based learning in the flow of work.

This is a good example of what Billet refers to as a structured work environment, which guides work and learning (methodical improvement) as a complex “social practice” through the four steps and the many tools of the PDSA cycle (Billet, 2002).

Amplifying Performance-Based Learning In The Flow Of Work With AI

The task of facilitating performance-based learning in the flow of work presents a considerable challenge for many Learning and Development professionals. The perceived dichotomy between learning while working and traditional, formal learning methods raises a multitude of queries.

The integration of learning silos and the adoption of an all-encompassing perspective on learning in organizations, which incorporates elements of formal, social, and informal learning, presents a potent strategy for L&D to make a tangible difference and demonstrate substantial business impact in the flow of work. This capability will be greatly amplified by AI-driven personal assistants in an unprecedented manner.

Artificial Intelligence-driven personal assistants represent a transformative force set to fundamentally alter our working and learning environments. The current concept of performance support, a predominantly passive form of guidance, is likely to undergo a radical metamorphosis into a synergistic blend of proactive personalized guidance, advanced search capabilities, content generation assistance, automatic task completion, and many more functions.

These AI-driven personal assistants enable L&D professionals to significantly expand their influence beyond the confines of formal learning scenarios, such as online or physical classrooms, into the realm of concurrent working and learning. This advancement is not just an encouraging development for L&D, but it also bears significant potential benefits for individuals, teams, and the wider organization.

Up Next: Unpacking L&D’s Role In The AI Era

As we reach the end of our exploration of AI’s potential to support performance-based learning in the flow of work, an intriguing question arises: how does AI intersect with the contemporary reality of performance support?

Hold on to that curiosity as we step into the next article of our series. We will be diving into the compelling world of amplifying performance support, with AI as our steadfast ally. What role does AI play in transforming “amplified performance support” into an integral part of our work routine? How can L&D professionals leverage AI during working and learning?

As you continue exploring the fascinating world of AI and its potential to revolutionize Learning and Development, we invite you to delve deeper with us. Visit our website Partners in AI for more in-depth information and insights, and the opportunities that AI brings to the corporate learning sphere.

The article series titled “Is AI The Bicycle Of The Mind?” serves as a prelude to my upcoming book, Value-Based Learning, offering a sneak peek into the insightful content the book will feature. Please note that all rights to the content in these articles and the upcoming book are reserved. Unauthorized use, reproduction, or distribution of this material without explicit permission is strictly prohibited. For more information and updates about the book, please visit: Value-Based Learning.

The author of this work holds intellectual property rights, and this content cannot be reproduced or repurposed without express written permission.

References:

- Arets, J., C. Jennings, and V. Heijnen. 2015. 70:20:10 Towards 100% Performance. Maastricht/London: Sutler.

- Bandura, A. 1977. Social learning theory. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Bersin, J. 2018. “A new paradigm for corporate training: Learning in the flow of work.” Bersin by Deloitte.

- Billett, S. 2002. “Critiquing workplace learning discourses: participation and continuity at work.” Studies in the Education of Adults, 34 (1): 56–67.

- Billet. S., quoted in Colley, H., P. Hodkinson, and J. Malcolm. 2002. “Non-formal learning: mapping the conceptual terrain. A Consultation Report.” Leeds: University of Leeds Lifelong Learning Institute.

- Council of Europe. “Formal, No- Formal and Informal Learning.”

- Colley, H., P. Hodkinson, and J. Malcolm. 2003. “Formality and Informality in Learning.” Learning and Skills Research Centre, London.

- Cross, J. 2007. Informal learning: Rediscovering the natural pathways that inspire innovation and performance. San Francisco: Pfeiffer, John Wiley.

- Edward Deming Institute.

- Moen, R.D., and C. Norman. 2010. “Clearing up myths about the Deming cycle and seeing how it keeps evolving.” Quality Progress 43: 22-28.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Reed, J., and A. Card. 2016. “The Problem with Plan-Do-Study-Act Cycles.” BMJ Quality and Safety 25 (3 ): 147–52.

- Wikipedia. Continual improvement process.

Image Credits:

- All images within the body of the article have been created/supplied by the author.