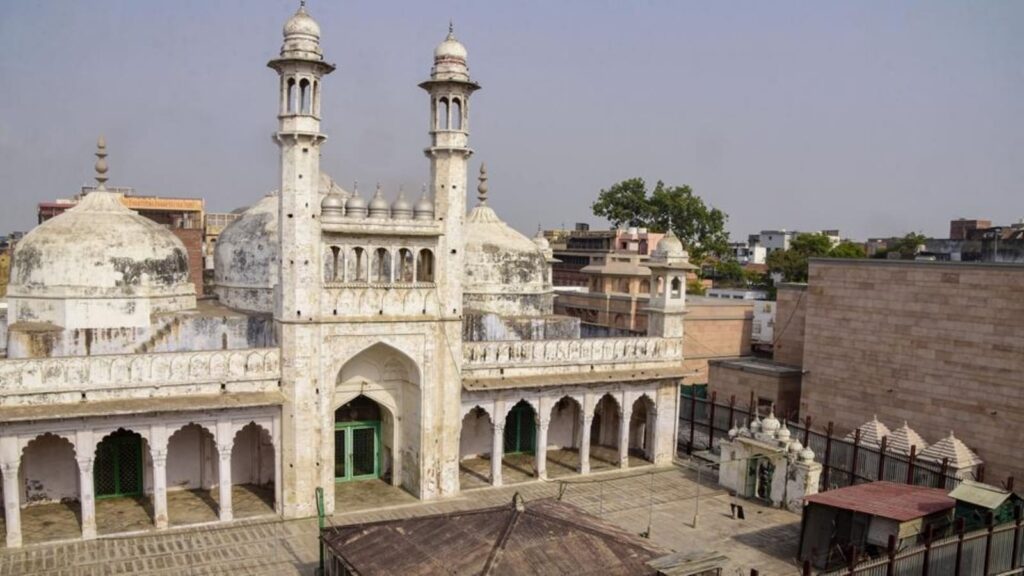

For almost two years now, a decades-old dispute between local Hindu and Muslim groups over the Gyanvapi Masjid that abuts the Kashi Vishwanath Temple in Varanasi has held the national centre stage. The first petition in the ongoing legal battle was filed in 2021, and the case has become the most important one of what has informally come to be known as the new temple movement (where Hindu groups have eschewed street protests for the courtroom, filing claims of ownership over Islamic holy sites in local courts in Agra, Mathura and Varanasi). Despite the attention and controversy around these claims, and utterances by minor politicians, the disputes remained strictly legal. Until now.

On Monday, in a conversation with news agency ANI, Uttar Pradesh chief minister (CM) Yogi Adityanath gave the dispute a distinctly political edge with what appeared to be a ringing endorsement of the Hindu petitioners — who argue that the mosque was built after partially demolishing a temple, with some asking for the rights to worship idols within the complex — and a call for the Muslim side to correct what he termed as a historical mistake. “If we call it a mosque, there will be a dispute,” the CM said, saying that he wanted a solution to the mistake and that the proposal should come from the Muslim side. Mr Adityanath is not only the most senior member of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to take a direct stand on a fractious and sensitive issue, he is also the CM of the state where the dispute originates and where it is being adjudicated. By his political stature alone, the comments acquire salience. His image as a Hindu strongman only adds credence to the belief that the issue will likely play a key role in political campaigns. In that sense, Mr Adityanath’s comments are a turning point that marked the transformation of a legal battle into a politico-legal movement, not unlike how the Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi dispute evolved.

This newspaper has repeatedly pointed out that the Gyanvapi case is important precisely because it has found a way around the guardrails of the 1991 Places of Worship Act, which was enacted to prevent exactly this eventuality. Unfortunately, the status of this law remains under a fog with neither the Centre clarifying its stand nor the Supreme Court taking a call on it. In this situation, expect more such religious disputes to be dredged up and inflame a communal sense of historical injustice. And, for these disputes to spill more and more from the courtroom into the political arena.

Experience unrestricted digital access with HT Premium

Explore amazing offers on HT + Economist