In Rajasthan, which votes today, the three-time chief minister (CM) Ashok Gehlot is battling history. Voters here have refused to vote for the incumbent government since 1993. Gehlot, 72, has sought to break this trend by making the polls a referendum on his record in office. The enormity of his challenge is evident from the fact that the Congress could only scrape through in the 2018 and 2008 elections, unlike its rival BJP which won by convincing margins in 2013 and 2003. The slant in the contest is because there are 54 assembly seats in the state that the Congress has been unable to win since 2008: The party has to win at least 100 of the remaining 146 constituencies in an assembly of 200 seats to win office.

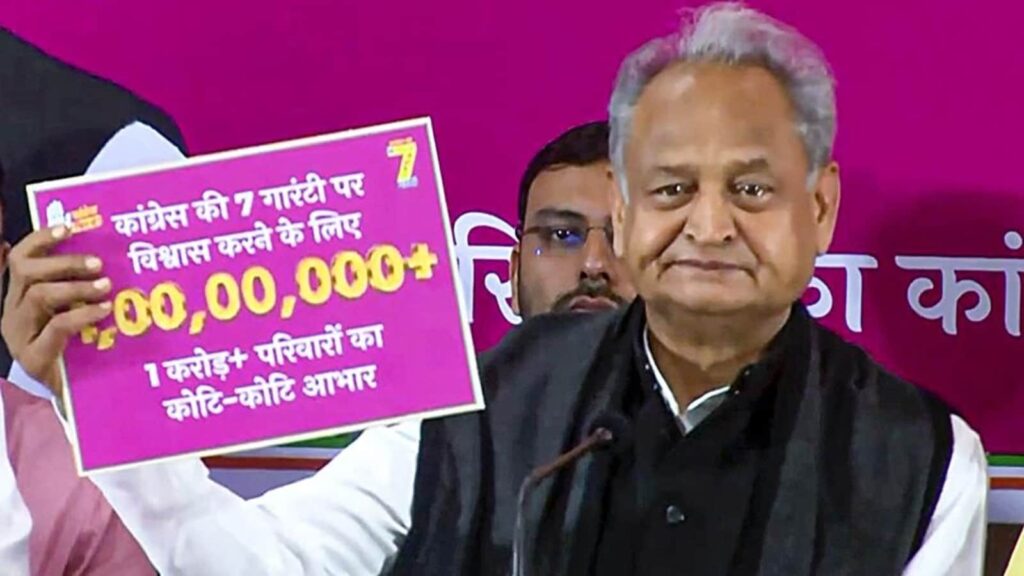

Rajasthan has largely stayed a bipolar polity for over three decades with the Congress and the BJP alternating in office. And for over a quarter century, Gehlot and Vasundhara Raje have been the faces of their respective parties. The BJP, however, has refused to project Raje as its CM nominee. Instead, it has offered a different binary to the electorate by turning the elections into a contest between Gehlot and Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The polls this time are a contest between the seven ”guarantees” of Gehlot/Congress and the promises of Modi/BJP. The Congress, following the model that won Karnataka for the party earlier this year, has released a manifesto heavy on welfare promises. These “guarantees” targeted multiple constituencies, especially women, with the promise of a monthly handout of ₹10,000 to women heads of families, LPG cylinders at ₹500, a ₹15 lakh insurance as protection from natural calamities and a scaled-up Chiranjeevi health insurance scheme. The BJP manifesto is a mixture of welfare and muscular nationalism that includes the promise of 250,000 government jobs in five years, a dole of ₹5,000, loan relief, and rural start-up fund to double farmers’ incomes but also deportation of Bangladeshis and Rohingyas and citizenship to children of displaced Hindus from Pakistan. If the BJP campaign flagged faith to polarise the electorate, the Congress sought to counter a Hindu consolidation with the promise of a caste census.

However, beyond the grand narrative of binaries, local and seemingly marginal factors complicate the poll picture and introduce a set of unknowns that can undo all calculations and predictions. For instance, small parties such as the Rashtriya Loktantrik Party, BSP, Bharatiya Adivasi Party, Bharatiya Tribal Party and the CPI (M) and the numerous rebels from the Congress and BJP may influence contests and even win a few seats. In 2018, independents and candidates from small parties won 22% of the votes and 27 seats. Gehlot’s magic was that he convinced the bulk of these MLAs to support his government, including during the 2020 rebellion by Sachin Pilot. Also, beyond the Gehlot vs Modi binary, the restive supporters of Pilot and Raje, now pushed into the background, can influence close contests, and may hold the key to government formation if no party wins with a runaway majority. A fourth win, however, will be remarkable for Gehlot, who had successfully fought off the BJP, Pilot and even the Congress high command to complete his term in office. However, this election may also see Rajasthan move away from the Raje-Gehlot binary.

Irrespective of the outcome, the Rajasthan campaign was significant since both parties sought a mandate based on their governance record. It is a good sign that parties are ready to compete on governance and respond to the demands of voters accordingly.

Continue reading with HT Premium Subscription

Daily E Paper I Premium Articles I Brunch E Magazine I Daily Infographics